|

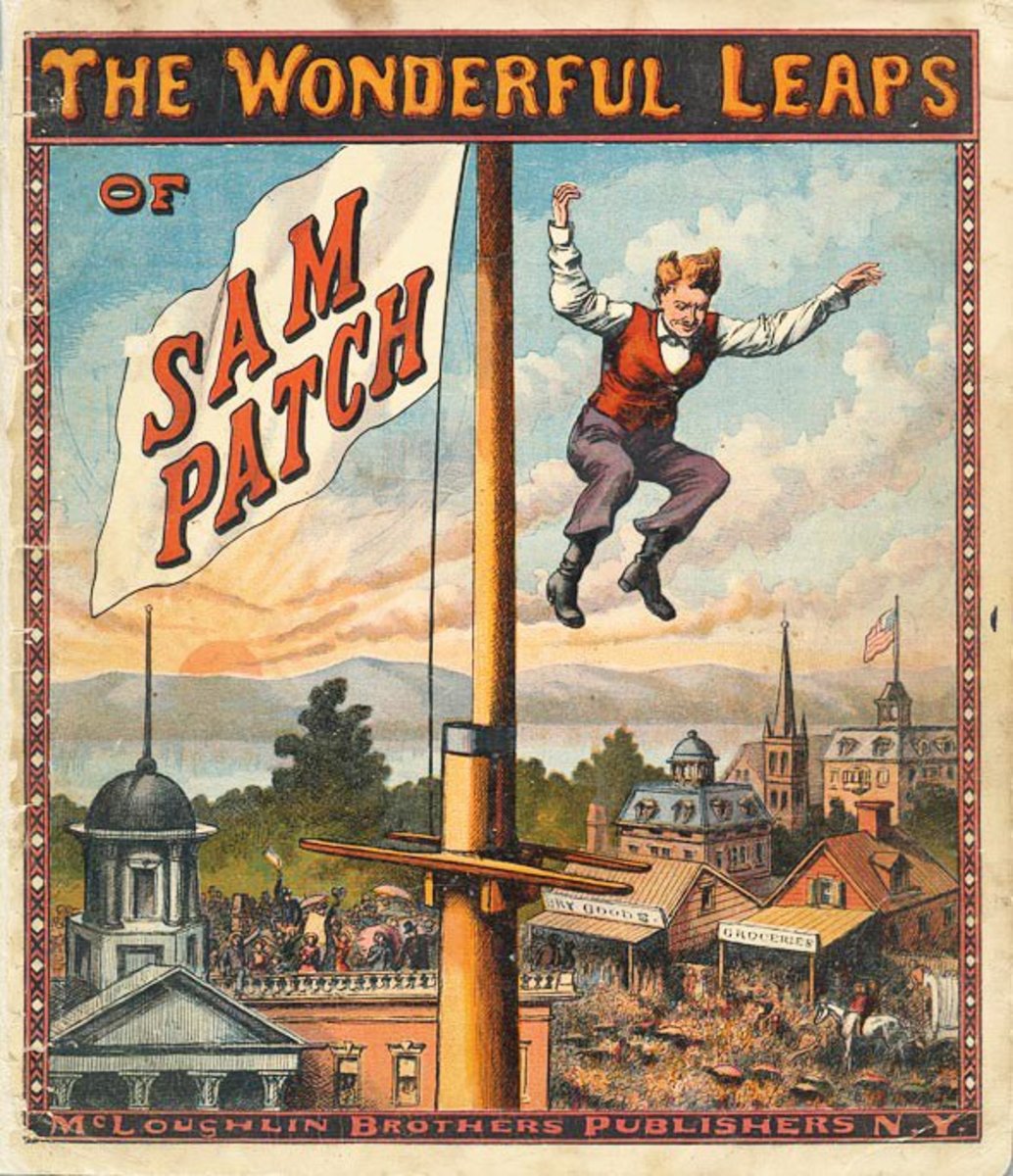

| Copy of a handbill from a play about the famous Sam Patch. |

The first person ever to

go over Niagara Falls and live to tell about it was a man named Sam Patch, who

accomplished the feat in October 1829. He earned the nickname the Yankee

Leaper as a result. His jump was part of a campaign to turn the Falls

into a more popular tourist attraction. It worked, too: a crowd of about

10,000 gathered to watch the 22-year-old Patch do it. Patch promised a second

jump because his first one was delayed due to technical problems—the ladder he

was to climb out to the middle of the falls on broke and had to be repaired—and

bad weather pushed his jump back to 4:00 in the afternoon. His second

jump saw conditions that allowed the jump and was much better attended, turning

Patch into a household name.

| Handbill from Sam Patch's final jump, 1829. This jump was not done as well as others. |

Patch had already

achieved a certain amount of fame for jumping off of waterfalls. Two

years earlier, in 1827, he’d jumped off of the Passaic Falls in New Jersey.

This turned him into a celebrity, making him very much in demand for

public appearances. He made a career out of jumping from waterfalls,

bridges and even ships’ masts. Patch was quite the draw, so when tourism

promoters in Niagara Falls reached out to him, they clearly knew what they were

doing. Patch the New Jersey Jumper transformed into the Yankee Leaper,

and he was going to cash in for all he could. Patch’s personal motto

“Some things can be done as well as others” entered popular currency, even

though it wasn’t exactly clear what this expression meant. It was printed

on handbills promoting Patch’s jumps, leaving the reader free to interpret it

as he or she wished.

The Passaic Falls were a

70-foot drop, which is much more manageable when compared to the daunting

167-foot drop at Niagara Falls, which Patch survived twice. Patch seemed

to be unstoppable—at any rate, it appears that he felt like he was. On

Friday, November 6, 1829, Patch went to the 99-foot Genesee Falls in upstate

New York and put on another well-attended spectacle. From the top of the

falls, he picked up his pet bear cub and threw it down the water. Once

the cub swam to the shore at the bottom of the falls, Patch jumped, and the

crowd went wild.

Though he drew some

paying customers, the haul from this jump wasn’t so great. Patch felt

this jump could raise more cash, so he announced he would jump again the

following Friday. To make it even more impressive, he had a wooden

platform constructed at the top of the falls, raising the height of his jump to

125 feet. Accounts differ as to whether Patch actually jumped or whether

he fell off, but witnesses (there were many) agree that Patch did not descend

feet-first like he usually did. From the surface of the water, spectators

heard a loud smack, but it was unclear what happened to Patch. He could

not be found.

This is the stuff that

legends are made of, so almost immediately rumors were flying that Patch had

slipped away to hide in a cave, savoring the excitement that his jump had

caused. The terrible truth was learned the following spring when a farmer

near Rochester found Patch’s frozen body in the Genesee River. Patch was

buried near Rochester. His small gravestone used to have a board placed

on top of it on which was written, “Sam Patch—Such is fame.”

Following his demise,

Patch’s celebrity continued. A series of plays about the Yankee Jumper

enjoyed well-attended performances well into the 1850s. President Jackson

even named his horse “Sam Patch” in honor of this daredevil.

Stunts in and around

Niagara Falls didn’t stop, either. Jumpers, swimmers, and tightrope

walkers challenged the falls, hoping to earn a little celebrity, themselves.

In 1901, on her 63rd birthday, a retired American schoolteacher named

Annie Edsen Taylor became the first person to successfully go over Niagara

Falls in a barrel. After she was fished out of the river, she announced,

“No one should ever do that again.” Since Taylor had no other means to

support herself in her retirement, she’d hoped to parlay her fame into a

lucrative income, but her public appearances never generated much interest, nor

did the never-seen film that reconstructed her jump. She attempted to

write a novel about the experience, which she never finished. Her

publicity manager ran off with most of her meager earnings from this tour.

Taylor died in poverty at age 83, having spent time working as a

clairvoyante, and attempting to cure people of their ailments using magnets, a

popular junk medical science of the day.

|

| Annie Edsen Taylor and her famous barrel, 1901. Atop the barrel: the cat who served as test subject before her jump. |

Stunts still go on at

Niagara Falls. Fifteen more people went over them in barrels after

Taylor; ten survived. There have been other jumpers, and even an attempt

to jump the Falls on a Jet Ski (which was fatal). In 2012, a man in his

forties became the fourth person to survive jumping over the falls unprotected.

He suffered lacerations, broken ribs and a collapsed lung. Though

there’s still an allure to going over Niagara Falls, it’s illegal, and you’ll

be arrested whether you wash up on the American side or the Canadian one.

Only if you survive. If you don’t, the authorities generally don’t

press charges.

Comments