The process of puffing grain is a very old one. The oldest known examples were discovered by

archaeologists in New Mexico. This

earliest puffed grain was popcorn, which has been around for at least 4,000

years. Early popcorn was smaller than

what we know today, with a popped piece roughly the diameter of a US penny.

Other

grains were never really puffed until much more recently. The next puffed grain to appear was invented

in 1901 by Dr. Alexander P. Anderson.

Dr. Anderson experimented with grains of corn starch, exposing them to

heat and pressure in test tubes. He

heated these grains in an oven, and later cracked them, which caused them to

explode into small puffs. This was the

invention of puffed cereal, which would be introduced to the world at the St.

Louis World’s Fair in 1904, billed as “The Eighth Wonder of the World”.

Sure, it’s grain—now with air!

Since

Dr. Anderson’s invention, puffed cereals have become a standard in the American

diet. Hundreds of different puffed

cereals line supermarket shelves today, with familiar names like Rice Krispies,

Kix, Cocoa Puffs, and Honey Smacks.

Many other brands have come and gone over the years. Few remember Happy Jax, introduced by Post

in 1948. Those who do remember it are

more likely to know it as Sugar Crisp, which Post renamed it the following

year.

Sugar

Crisp was puffed wheat covered with a sugary glaze. The cereal’s mascot was a cheerful bear cub called Sugar Bear,

who served as an eager cheerleader for Sugar Crisp and the benefits of eating

breakfast every day. It was marketed as

a health food, promoted in language that might seem a little confusing to modern

consumers. For a while in the 1950s,

the tag line was, “For breakfast it’s dandy, for snacks it’s like candy!”

1950s Sugar Crisp cereal ad.

Walk

down today’s supermarket cereal aisles and you’ll see many puffed cereals, with

recipes that haven’t changed much in a half century or more. One thing you won’t see is the word sugar,

which has been scrubbed from the names of most, if not all, American breakfast

cereals.

Early

promotions of cereals touted them primarily as a breakfast food, but also as a

snack food, and sometimes as candy.

Sugar Crisp’s early advertising showed that Post saw no conflict in

calling something a healthy breakfast food and candy at the same time. The public didn’t seem fazed by this,

either.

Sugar

Crisp (later renamed Super Sugar Crisp) was always marketed toward

children. Its first packages featured

the Three Bears on it (but quickly reduced it to one bear). This bear was always called Sugar Bear. Sugar Bear’s early personality was more that

of an eager child, but in 1965, he was given a turtleneck, a new voice and a

new personality. Voiced by actor Gerry

Matthews, Sugar Bear sometimes sounded more like Bing Crosby, sometimes more

like Dean Martin.

Post Sugar Crisp box with the first appearance of the new

Sugar Bear, 1964 (left), and the more familiar version, 1965 (right).

The

television commercials were successful, but in 1964, Post tried something

new. Working with Ed Graham

Productions, CBS, and General Foods, a new Saturday-morning cartoon called Linus

the Lion-Hearted was launched. Linus

was just one of five characters who appeared in the lineup for this ensemble

series. The characters were actually

Post cereal mascots, promoting five different cereals, including postman

Lovable Truly for Alphabits, young boy and offensive Chinese stereotype So Hi

for Rice Krinkles, and Sugar Bear for Sugar Crisp. The show was a half-hour collection of cereal ads, with time out

for commercial breaks. Linus

produced 39 episodes over two seasons, and then sold the show to ABC, who aired

it in reruns until 1969. The show was a

successful advertising gimmick—too successful.

The reason ABC took it off the air was because it had to. The FCC ruled in 1969 that TV shows couldn’t

have advertising mascots as their characters, so that was the end of Linus.

Linus the Lionhearted record. Listen to Linus with all his cereal-mascot friends.

Advertising

for Sugar Crisp was picked up by Jay Ward Productions, which had produced TV

cartoon hits like Crusader Rabbit, Rocky & Bullwinkle, and George

of the Jungle. Jay Ward made dozens

of cartoons for Sugar Crisp (as well as Quisp, Quake, King Vitamin, and their

most famous mascot, Cap’n Crunch) through the 1970s, seeing the brand into the

Super Sugar Crisp name. Around this

time, events would require a new name change for Super Sugar Crisp.

In

1977, research done by dentist Ira L. Shannon showed that a number of breakfast

cereals were made mostly of sugar. This

should come as no great surprise where some are concerned. Super Sugar Crisp has sugar in its

name, and had never tried to cover that up (though it had been a while since it

promoted itself as candy). The highest

sugar content of any breakfast cereal on the market was Fruity Pebbles, which

was 55.1% sugar. Cocoa Pebbles was

second, at 53.5% sugar, followed by Honeycomb, at 48.8% sugar. Super Sugar Crisp was actually in fourth

place, a mere 40.7% sugar. For context,

a Milky Way candy bar is 28.8% sugar, and soda pop a mere 4.2%.

A

small law firm in San Francisco filed a lawsuit against Post and other cereal

manufacturers. They sued them over

these “candy breakfasts”, claiming that their advertising campaigns “blur the

distinction between fantasy and reality to the point where children cannot

distinguish” fantasy from reality. One

of the firm’s attorneys, Sidney Wolinsky, said the suit was filed because

“Pitching food products to children on TV is like shooting fish in a

barrel. They’re creating a nation of

sugar-junkies with a sugar habit.”

Meanwhile, the Boston-based public advocacy group Action for Children’s

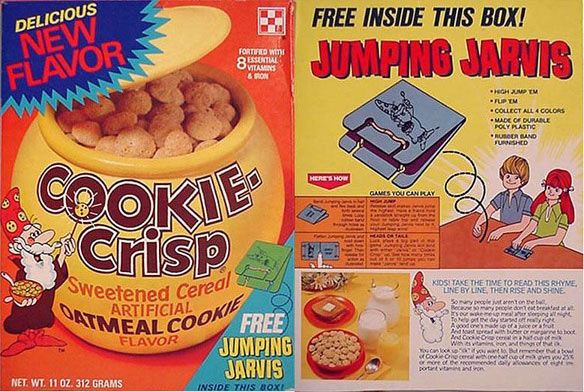

Television filed a lawsuit against Ralston Purina against the new cereal Cookie

Crisp, which was 46% sugar and promoted itself as a breakfast that “tastes just

like cookies”. (Its TV ads showed a

jolly wizard named Cookie Jarvis tempting kids with the cereal, causing them to

cry out, “Cookies for breakfast? No way!”

as a bowl full of miniature cookies appeared on the table before them.)

Hey, kids! Cookies

for breakfast!

The

lawsuits, in the end, did not bring these brands down, but they did bring about

change. Cereals (and all other

products) are required to state on the packaging just how much sugar they

contain, which is why this information appears on packages today. Another result was a number of cereals

dropping “sugar” from their names.

Sugar Puffs became Golden Puffs.

Sugar Smacks became Honey Smacks.

Sugar Chex ceased to exist. And

Super Sugar Crisp became Super Golden Crisp.

Same bear, same recipe, same sugar content, but now with accurate

labeling.

Sugar

Bear has not disappeared. He was never

renamed, and Post doesn’t try to cover up his name. But if you go to Post’s website today and check out the history

of Golden Smacks section, nothing states that the cereal was ever called

anything but Golden Smacks.

Comments

Ian M