In 1840, the United States was facing its 14th presidential election, ready to give President Martin Van Buren a second term, or to elect its ninth president. The feeling was that the Democratic-Republicans (or the Democrats, as they came to be known) would win again. Of course they would! Only three times had the United States elected a man who wasn’t a Democratic-Republican. There was John Adams, a Federalist, elected in 1796, and George Washington, elected in 1789 and reëlected in 1792, who claimed no party affiliation. For forty years, the Democrats had had a solid grip on the Executive Mansion (or, as it would later be called, the White House). Every election following the creation of the Electoral College in 1804 had gone for the Democrats. Could nothing be done to break their grip on power?

The Whig Party hoped there might be something it could do. The Whigs were founded in 1833, so this was to be their second presidential election. Their first presidential election, in 1836, didn’t go so well. Their strategy was creative, if nothing else. The Whigs nominated four men for president, each from a different region of the country. They hoped that each candidate would have sufficient appeal in each region to defeat Van Buren. Then, when the Electoral College met, the supporters of the four Whig candidates would pool their votes and decide on the best Whig to win. It was a great… failure. The divided Whig ticket failed to generate enough strength to beat Vice President Van Buren, who sailed into office on the heels of retiring President Jackson.

The Whigs felt the need to approach the election of 1840 overly cautiously. They decided to hold their nominating convention in the fall of 1839—over a year before the actual election—and they nominated William Henry Harrison, a celebrated general who’d gained fame in the Indian Wars in Indiana between 1811 and 1813. In these wars, he’d defeated Chief Tippecanoe, which led to Harrison getting “Tippecanoe” as his nickname. With John Tyler selected as his running mate, the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too!” was born.

It was a colorful election, using campaign tactics for the first time that would become staples in American politics. Besides Harrison’s military career, much was also made of his humble origins. He was said to have been born in a log cabin on the frontier in Ohio, and worked his way up from nothing. This wasn’t true—Harrison was actually born of a well-to-do family in Virginia, but the voters didn’t need to know that. When Harrison started to appear to be a threat to President Van Buren, charges that the Ohio general was a drunk started circulating. In response, Harrison supporters started handing out bottles of hard cider encased in miniature log cabins. The idea was to neutralize the effects of the “drunk” charges. It also helped Harrison in the West, because people drank whisky and hard cider a lot more in the West, since clean water was still pretty hard to come by on the frontier, which was still developing its infrastructure.

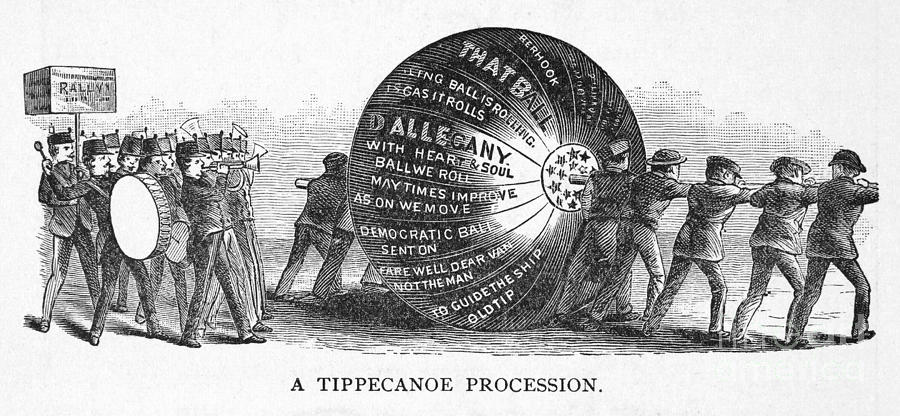

Another interesting campaign gimmick Harrison’s supporters used was the Harrison Ball. The Ball was maybe eight or nine feet tall, held together inside with wooden spokes, and covered with paper or tin on the outside. The paper and tin had pro-Harrison slogans written all over it. Men would roll this ball from one town to another, cheering about how great Harrison was. (In the days before television or radio, this was high entertainment!) This is the origin of the expression “Keep the ball rolling!” There are no photographs of this ball, of course, but this cartoon gives you an idea what it looked like:

In hindsight, the Whigs probably didn’t need to try so hard in that election. Soon after Van Buren took office, the Panic of 1837, one of America’s worst financial crises, took place. Plus Van Buren was opposed to slavery, an issue that was dividing the Democratic-Republican Party at the time. Many Democrats also wanted Van Buren to annex the Republic of Texas, but he refused, on grounds that it would admit a large slave state to the Union, and probably lead to war with Mexico. (When Texas was finally annexed in 1845 by President Polk, a Democrat, Van Buren’s fears would be proved correct.)

In the end, Harrison defeated Van Buren handily in the Electoral College, 234-60, and won the popular vote by about 53%. It was a solid victory, and led President William Henry Harrison to enjoy his place in history as the first Whig to be elected president, the oldest person to be elected president (a record broken by Ronald Reagan in 1980), and the first president to die in office, when he submitted to pneumonia one month after his inauguration.

The election of 1840 is also known for having produced a lot of campaign songs. The tradition of the campaign song continued into the 1960s, but it used to be quite popular. Typically a campaign song wasn’t an original composition, but a popular song with new words written for it. Here’s a popular Harrison song from the 1840 campaign, written to the tune of the popular song “The Little Pig’s Tail”, and recorded in 2003 by They Might Be Giants:

And in the

interest of bipartisanship, here’s a pro-Van Buren song. Well, it’s more

anti-Whig than pro-Van Buren, but still: I’m trying to be fair. (You

probably know the tune.)

Comments

I learn something new every time I read your blog. Keep up the great work!