The seventh planet in the Solar System is named... George?

Ancient astronomers discovered the first five planets. (Six, if you count Earth, which I don't, since Earth was "discovered" well before there ever was such a thing as an astronomer.) The word planet comes from the ancient Greek planan (πλαναν) meaning to wander. The word moved from Greek to Latin to French and finally to English, through a bit of wandering itself. These special stars got this wanderer name because they seemed to wander around the sky, while the other stars remained fixed, more or less, only moving when the rest of the sky did.

There were two more planets wandering around in the sky, of course, that were not really known on Earth. They were harder to see, since they were so far out, despite their being gas giants. These other two planets aren't as big as the two known gas giants. Saturn is about 9.5 times the size of Earth, and Jupiter is about 11 times the size of Earth, and both are closer. The two outer planets are each about 4 times the size of Earth. That's why astronomers kept missing them.

They didn't miss them all the time, though. The seventh planet, out past Saturn, was spotted on occasion over the past two millennia. Its first recorded sighting was by the Greek astronomer Hipparchos in 128 BCE, which he noted in his catalog of stars. This planet wasn't regularly seen (or, at least, sightings of it weren't regularly recorded) for a good while afterward. The next sighting of the planet came in 1690, when English astronomer John Flamsteed also mistook it for a star, seeing it six times and naming it 34 Tauri. 34 Tauri was spotted again, twelve times between 1750 and 1769 by French astronomer Pierre Charles le Monnier.

In 1781 the object was spotted again, this time by English astronomer William Herschel. It didn't look like a star to him, but he wasn't quite sure what it was. Herschel reported it looked maybe like a comet or a planet. Despite there being no tail on the object, Hershel referred to it as a comet. Other astronomers throughout Europe took an interest, and a consensus rapidly formed that this new object was not a star or a comet, but rather "a Primary Planet of our Solar System" in 1783. King George III was thrilled that his country had made this discovery, and gave Herschel a £200 stipend so he could move to Windsor, closer to London, that the Royal Family might be able to look through his telescopes.

|

| William Herschel, who discovered Uranus, much to the delight of snickering schoolchildren. |

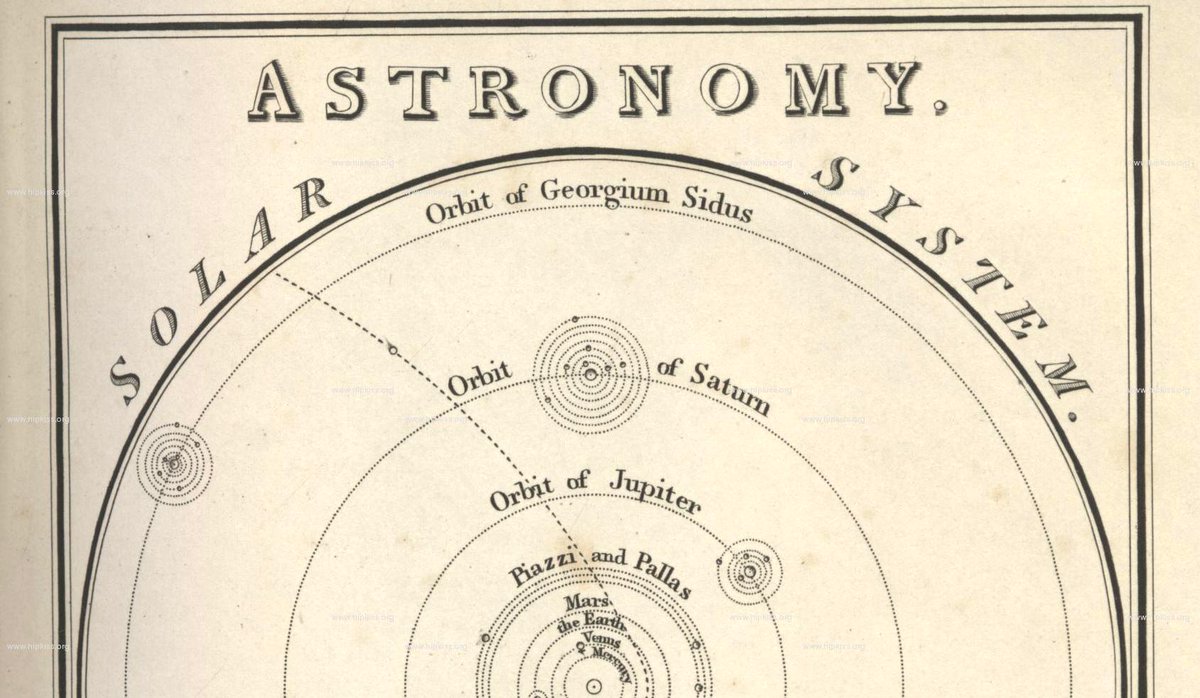

This was momentous: it was the first discovery of a planet by an astronomer. Any other planet could be seen at night by anyone with a decent pair of eyes, but this was something new. Naming planets wasn't the kind of thing anyone was used to doing. What were the conventions? All the known planets (except Earth) sported the Latin names of the ancient gods. Should this new planet be named for a god, too? Hershel considered it, but his colleague, Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne, proposed that this new planet be named George. Seriously, he did. Specifically, Georgium Sidus, or "The Georgian Planet", after His Majesty King George III.

Not surprisingly, this name appealed less to the world outside England. French astronomer Jérome Lalande suggested the name Herschel, feeling it was only appropriate to honor the planet's discoverer. Swedish astronomer Erik Prosperin kept within the classical gods theme and suggested Neptune. This had a certain resonance in Great Britain, where some embraced the idea that this compromise could serve to salute the British naval victories in the American Revolution, which was just then drawing to a close. The spirit of compromise was spoiled by some when the names Neptune George III or Neptune Great Britain.

Another suggestion came from German astronomer Johann Elert Bode, who proposed the name Uranus, after the Greek sky god. Uranus is a Latinized version of the Greek Ouranos, which kept all the planets in the sky consistent with Latin-sounding names, even though this new name was Greek. (The Latin name for Uranus is Caelus.) Part of the appeal, Bode saw, was how well it worked with the other planets: in mythology, Saturn is the father of Jupiter, so why not call the new planet Uranus, who is the father of Saturn?

Agreement on what to call the planet took a while. Different publications and scientific institutions around Europe had different ideas (though the main disagreement was between England and everyone else). Uranus gradually became the favored choice. Scientist Martin Klaproth of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences even selected the name of a new element he discovered in 1789 with a mind to support Bode's name for the new planet: uranium.

|

| An old star chart showing the seven known planets, naming Georgium Sidus, or Planet George. |

In 1850, Her Majesty's Nautical Almanac Office officially decided to adopt the name Uranus in its publications, finally dropping the name Georgium Sidus. This was the last of the holdouts: all of Europe and the Americas were now referring to the seventh planet as Uranus. Not all countries have adopted this exact name. In China, the Koreas, Mongolia, Japan and Vietnam, the name used translates as "Sky King Star", which admittedly isn't a far cry from the description of who Uranus is. However, the Thai name for the planet is Dao Mariyatu, a name that derives from the Sanskrit word for death. The Sanskrit word also refers to Mrtyu, or Māra, a goddess who is the personification of death and temptation. I don't know why Thai astronomers went with something so different from what the rest of the world settled on, but they're at least consistent with the trend to name planets after gods.

Comments