John F. Kennedy—known to his friends as “Jack”—is remembered for a lot of things. There was his service on PT-109 during World War II, his popular presidency that was contemporarily referred to as “Camelot”, the Cuban Missile Crisis, a tragic and violent assassination, and a series of train robberies. Okay, that last item comes off as a little… incongruous, I’ll admit. Presidents don’t usually get up to criminal activity until after they’ve been in office, so where would Kennedy find the time to slip away from the Oval Office and go stick up trains?

Well, there were actually two different John F. “Jack” Kennedys. The better-known one was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1917. The train robber was born somewhere in Missouri, sometime in 1870. (Sorry, but that’s as specific as his biographers are able to get.) The first Jack Kennedy’s fame was eclipsed considerably by the second Jack Kennedy. Despite identical names, the two are not known to be related. (Having the same name as a famous train robber didn’t impede President Kennedy from winning Missouri in the 1960 presidential election. Or, at least, it didn’t impede him much.)

Kennedy, known as the “Quail Hunter”, carried out his robberies with his face covered. Despite his disguise, his identity was an open secret. In the 1890s, he successfully carried out robberies of at least seven trains carrying either mail or goods. Between 1896 and 1898, he went to trial three times. He avoided conviction each time, typically by bribing jurors, and by hiring very capable (if ethically challenged) lawyers.

In 1899, the Quail Hunter was arrested a fourth time. This followed a botched train robbery near Leeds, Missouri. Kennedy joined forces with Jesse E. James for this one. James was the son of the celebrated outlaw Jesse James (not the actor), who was still a beloved figure years after his murder by Robert Ford in 1882, a bounty hunter who’d joined the James Gang specifically to collect the reward. Shortly after the failed train robbery, Kennedy stepped into a barber shop for a shave. During the shave, a police officer entered the shop to arrest Kennedy. Kennedy, probably intending to deny the police officer the $500 reward (worth just over $14,000 in 2017 dollars), testified that the barber had the “intention to take his prisoner to the county jail after he had finished his tonsorial work.” The barber’s name? Tom Hanks. No, not that Tom Hanks! But yes, his name really was Tom Hanks.

Left: Tom Hanks the actor. There is no record that he’s ever cut anyone’s hair in Missouri.

Left: Celebrated outlaw Jesse James.

Well, there were actually two different John F. “Jack” Kennedys. The better-known one was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1917. The train robber was born somewhere in Missouri, sometime in 1870. (Sorry, but that’s as specific as his biographers are able to get.) The first Jack Kennedy’s fame was eclipsed considerably by the second Jack Kennedy. Despite identical names, the two are not known to be related. (Having the same name as a famous train robber didn’t impede President Kennedy from winning Missouri in the 1960 presidential election. Or, at least, it didn’t impede him much.)

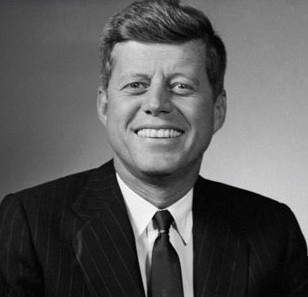

Left: John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States (1961-63)Right: A theatrical poster for a Tom Mix western about a train robbery. (Actual photos of John F. Kennedy the train robber do not appear to exist, nor did Kennedy use horses to rob trains.)

John F. Kennedy is remembered as “the West’s last notorious train robber”. Despite this colorful title, Kennedy carried out most of his robberies in Missouri. His career started there in the 1890s, when he trained to be a locomotive engineer. It was steady work that paid decently, but Kennedy soon got it in his head that he could do better for himself. He knew what kinds of cargoes the trains carried, and as an experienced engineer, he had plenty of inside knowledge that helped him pull off these robberies.Kennedy, known as the “Quail Hunter”, carried out his robberies with his face covered. Despite his disguise, his identity was an open secret. In the 1890s, he successfully carried out robberies of at least seven trains carrying either mail or goods. Between 1896 and 1898, he went to trial three times. He avoided conviction each time, typically by bribing jurors, and by hiring very capable (if ethically challenged) lawyers.

In 1899, the Quail Hunter was arrested a fourth time. This followed a botched train robbery near Leeds, Missouri. Kennedy joined forces with Jesse E. James for this one. James was the son of the celebrated outlaw Jesse James (not the actor), who was still a beloved figure years after his murder by Robert Ford in 1882, a bounty hunter who’d joined the James Gang specifically to collect the reward. Shortly after the failed train robbery, Kennedy stepped into a barber shop for a shave. During the shave, a police officer entered the shop to arrest Kennedy. Kennedy, probably intending to deny the police officer the $500 reward (worth just over $14,000 in 2017 dollars), testified that the barber had the “intention to take his prisoner to the county jail after he had finished his tonsorial work.” The barber’s name? Tom Hanks. No, not that Tom Hanks! But yes, his name really was Tom Hanks.

Left: Tom Hanks the actor. There is no record that he’s ever cut anyone’s hair in Missouri.

Right: Tom Hanks the barber. There is no photograph available of him, so maybe he looked like this. Who knows?

Due to public sentiment still running strongly in favor of Jesse E. James’s famous father, both robbers were acquitted. Soon after that, the Quail Hunter went out and committed yet another train robbery, but this time, the conviction stuck. He was tried and convicted and sentenced to 17 years in the Missouri Penitentiary, but he got out after a mere 12 years for good behavior. For the next ten years, Kennedy stayed out of trouble, but he couldn’t stay away from his old profession. In 1922, he started preparing for another job. By this time, he was famous, and that was his downfall. A railroad employee spotted Kennedy on the line that ran from St. Louis to Memphis. The employee noticed Kennedy making frequent trips on the line, and making frequent stops. This tipped off the railroad, which decided that the night train was the one to watch, since it made frequent deliveries of cash to Memphis from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank.

Left: Celebrated outlaw Jesse James.

Center: Similarly celebrated outlaw Jesse E. James.

Right: Law-abiding actor Jesse James (no relation).

On November 3, 1922, Kennedy, with his accomplice Harvey Logan, another former railroad employee, boarded the night train in St. Louis. Somewhere near Wittenberg, Missouri, the two outlaws entered the locomotive, guns drawn, and ordered the engineer and the fireman to stop the train. This train wasn’t carrying cash shipments from the Federal Reserve, but there were sacks of mail, which also made for a good target for train robbers. After taking the mail, the robbers decoupled the locomotive from the railroad cars and headed off down the tracks toward Wittenberg. About 150 yards north of the Wittenberg station, the robbers jumped out of the locomotive with the stolen mail as the locomotive ran wild down the tracks. Nearby the two had parked their car, which they planned to drive away in. Waiting for them in the brush near their car were six postal inspectors, three railway special agents, and two deputy sheriffs. The moon was full that night, and they could all see each other clearly. The posse told the robbers to surrender, but Kennedy and Logan decided to shoot their way out. They drew their guns, but before they could squeeze off a shot, they were mowed down, themselves. They were killed on site, their hands still clutching their revolvers. All the mail was recovered.

While the train was stopped, the robbers had selected about 100 registered letters to steal from the mail. These were the ones most likely to contain cash. It’s unknown if the letters actually did contain cash, since all of them were recovered, and sent to their intended recipients.

Comments