Quick: who invented the airplane? If you’re an American, you no doubt thought

of the Wright Brothers. If you’re from

New Zealand, you probably thought of Richard Pearse. If you’re from Brazil, you no doubt thought

of Alberto Santos-Dumont. All three are

widely held to be responsible for the invention of the flying machine.

A few of the best-known pioneers of flight. Left to right: Orville Wright, Wilbur Wright, Alberto Santos-Dumont, Richard Pearse

National pride might cloud

people’s judgement. And since people had

been trying to invent the airplane for years, it’s fair to say that whoever deserves

credit for finally inventing it owes a lot to those who worked on the problem

before. The Wright Brothers’ flight took

place on December 17, 1903, and lasted all of 59 seconds. Richard Pearse’s flight beat them by about

nine months, taking place on March 31, 1903.

Witnesses claim that Pearse flew his plane roughly three meters off the

ground and crashed it into a hedge.

Pearse had worked on creating an airplane for years, but the evidence

that he was successful at it is disputed.

Pearse himself said that he never attempted any serious attempt at

building a flying machine until 1904, and never claimed that his plane flew,

despite so many New Zealanders who today think otherwise. Pearse is hailed as a kind of national hero

of New Zealand today, and many New Zealanders are annoyed by what they perceive

as the “myth” that the Wright Brothers flew first. Pearse himself said in a 1915 letter that the

airplane was “the product of many minds” and that “pre-eminence will

undoubtedly be given to the Wright Brothers.”

One of the other minds that

worked on the airplane was Alberto Santos-Dumont. Santos-Dumont was the youngest son of a Brazilian

coffee plantation owner by the name of Henrique Dumont. Dumont did well in no small part due to the

many small labor-saving devices he built that streamlined and increased

production. A fall from a horse

partially paralyzed him, so in 1891 he sold the plantation and moved to Paris

with his wife and Santos-Dumont, where he felt he would have better luck

finding treatment for his condition.

Henrique Dumont did not find the help he needed and returned to Brazil,

where he died the next year.

Alberto Santos-Dumont, on the

other hand, grew attached to Paris and stayed there. He studied science and engineering there

under private tutors. He had long been

interested in these subjects, a passion fueled by his exposure to Jules Verne

novels as a boy. Santos-Dumont said he

used to look up at the sky over his father’s coffee plantation and imagine

flying. In Paris, he got his first

chance. The owner of a hot air balloon

told him he would take him up in the air for an afternoon for the price of

1,200 francs, which was a lot of money in those days. Santos-Dumont balked at this, saying that was

a lot of money to spend on something he might not like, and that if it turned

out he did like it, that was a lot of money to be tempted to spend to do it

again.

Santos-Dumont didn’t give up

on balloons, though. Taking inspiration

from Swedish balloonist Salomon Andrée’s attempt to fly a balloon to the North

Pole, Santos-Dumont started working on balloons of his own. He designed a hot air balloon that was

remarkably small, yet functional. It had

a small basket beneath it, only large enough to hold one person. He dubbed his balloon the Brésil, the French word for his native

country, and took it on many flights.

|

| Santos-Dumont in his first steerable balloon, the Brésil, 1896 |

After a while, he started

working on designing a balloon that he could steer. A steerable hot air balloon had actually been

done in 1884, but work on this design ground to a halt due to the inventors’

lack of funds. Santos-Dumont came up

with two designs for an airship held aloft by a ballonet. A ballonet is a balloon inside a

balloon. The balloon on the inside is

filled with lifting gas, usually hydrogen or helium. The larger, outer balloon is filled with air.

When the outer balloon is filled with

more air, it compacts the lifting gas, which makes the ballonet heavier. Letting air out of the outer balloon allows

the lifting gas to expand and makes the ballonet lighter. This gives the pilot control over whether the

balloon is ascending or descending. This

technology dates back to 1783, invented by Jean Baptiste Meusnier, a lieutenant

in the French army, whose airship project ultimately did not succeed. His ballonet idea was his real success, and

had been tinkered with by inventors up to and after Santos-Dumont. Santos-Dumont’s 1898 airship featured an

elongated ballonet, a revolutionary idea, but a difficult one to make

work. This airship crashed, as did his

second one, with a similar design, in 1899.

The elongated design couldn’t hold the lifting gas’s pressure as well as

a round ballonet could. He had more

success with his third design, which he had flown a number of times by the end

of 1899. He kept it at the Aéro-Club de

Paris’s flying grounds at Parc Saint Cloud, where he had an airship shed and a

hydrogen-generating machine.

The inventions of

Santos-Dumont and others were starting to generate excitement. Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe, known as “the Oil

King of Europe”, announced in April 1900 a prize of 100,000 francs to the first

person who could build an airship that could fly from the Parc Saint Cloud to

the Eiffel Tower and back in 30 minutes or less, before October 1, 1903. Santos-Dumont made a number of attempts with

a new design of his airship which he dubbed the Santos-Dumont. The first one

failed, as did the Santos-Dumont 2, the

Santos-Dumont 3, and two more

airships (guess what they were called).

On October 19, 1901, the Santos-Dumont

6 made its attempt. Crowds gathered

to watch, as did the adjudicating committee for the prize, and Henri Deutsch de

la Meurthe himself. The Santos-Dumont 6 took off for the Eiffel

Tower but after nine minutes, its engine failed. Santos-Dumont had to climb over the edge of

the airship’s gondola in order to restart the engine. He succeeded, and rounded the Eiffel Tower,

then made his way to the finish line, crossing it after 29 minutes and 30

seconds. When he got there, he had some

trouble mooring the airship. The prize

committee felt he took too long and denied him the prize. The crowd was outraged, but Henri Deutsch de

la Meurthe announced that he was satisfied with Santos-Dumont’s results, and

overrode the committee. The wealthy

aviator magnanimously gave half the prize money to his crew, and the other half

to the poor of Paris. Victory!

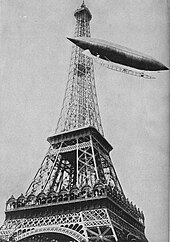

|

| The Santos-Dumont 6 rounds the Eiffel Tower on its famous flight, 1901. |

Santos-Dumont was

understandably the most famous aviator of the day. He flew his airships around Paris quite a

bit, and also traveled with them internationally, taking them to the Louisiana

Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in 1904, where the airship he brought arrived

damaged. Sabotage was suspected, but

nothing was proven. A similar incident

happened later that year in London. He

returned to Paris after this. In Paris,

he complained to his friend Jacques Cartier about the difficulty of checking

his watch while having to handle the controls of his airship. Cartier soon afterward invented the

wristwatch. This fashion caught on

quickly, since Parisians were already copying Santos-Dumont’s style, adopting

his high shirt collars and Panama hats.

Santos-Dumont went on to work

on heavier-than-air aircraft, with fixed wings and no balloons. His first successful design debuted in 1906,

more than two years after the Wright Brothers’ famous heavier-than-air flight

at Kitty Hawk. Santos-Dumont’s later

aircraft were small and never flew very far.

Santos-Dumont’s personal flying record was 220 meters, which he achieved

in 1906, when he became the first person to be filmed flying in an

airplane. At the time, the Wright

Brothers claimed to have flown an aircraft a distance of 30 miles, which

Santos-Dumont dismissed as a bluff.

After crashing one of his airplanes in 1910, Santos-Dumont announced he

was retiring from flight. He became

somewhat reclusive in his retirement. It

was rumored that he had suffered a nervous breakdown from overwork, but the

more likely explanation was the onset of multiple sclerosis. Santos-Dumont also suffered from depression

later in life. He took up astronomy as a

hobby, and remained interested in science.

He eventually returned to Brazil in 1931. Due to his illness and his depression over

the use of aircraft used in warfare during Brazil’s 1932 Constitutionalist

Revolution, he hanged himself. His body

lay in state for two days in the São Paolo Cathedral and received a state

funeral. He was 59 years old.

To this day, Brazilians are

often baffled by Americans claiming the Wright Brothers were first in

flight. Really, the difference comes

down to what you find to be important.

Often the Wright Brothers’ flight will be cited as the first heavier-than-air flight, which is a big

deal, but the tendency to abbreviate that to “the first flight” is arguably

inaccurate. Santos-Dumont’s airship was

a balloon you could steer and was propelled by an engine—but why does it make

any difference that it was lighter than air?

Perhaps Richard Pearse made the best point about it when he credited the

invention of artificial flight as “the product of many minds”. The modest Pearse, who never claimed he

accomplished what so many of his fellow New Zealanders believe he did, seemed

to recognize that where the invention of the airplane is concerned, there are

no giants, but we’re all standing on others’ shoulders.

|

| New Zealand engineer Ivan Mudrovcich's 2013 replica of Richard Pearse's aircraft. None of Pearse's original crafts exist today. |

Comments